I’ll always remember the desert for its vastness — for it’s bare and exposed landscape and the way it was almost maddeningly empty. But my introduction to it was dark — dark and enclosed… maddeningly empty in another way.

It was a moonless night, and without the lights of a town to help soften the blackness, I could barely see anything past the headlights of Jesse’s beat-up Subaru. Just the steady flow of stubby shrubs and shadowy mounds that stopped the starry sky in its tracks.

“Yeah, it’s an old silver mine, or maybe lead. Matt and I have been in a few times — we’re trying to find the second entrance.” Chad said casually as he fiddled with his headlamp in the front seat.

I’d only just met the group of scallywags I was riding with to the War Eagle Mine in Tecopa, California. There were three in total, all young men who lived and worked at Cynthia’s Desert Lodgings. Chad was by far the most talkative and chattered away like a squiffy at a barn dance as Jesse, in the driver’s seat, nodded along to Chad’s musings, occasionally chiming in to correct his friend’s memory or offer his thoughts. In the backseat with me, sat our silent compadre and the biggest mystery of the bunch. Matt seemed friendly enough but I was hard-pressed to get more than a few words out of him.

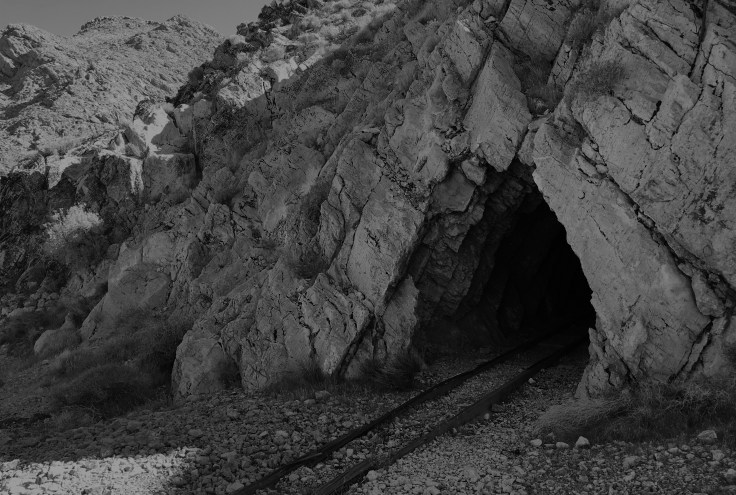

“That’s the turn!” Chad announced suddenly and Jesse slammed on the breaks to swing left onto an unpaved, sorry excuse for a road. We moved slowly, avoiding rocks the size of our heads and easing our wheels through giant cavities in the dirt until our headlights revealed a tunnel in the rock-face of the mountain, framed carefully by thick, wooden beams — the entrance of the mine.

“Here we are,” Chad said, casually zipping snacks and supplies into a dusty, yellow backpack. The night was chilly but as we prepared to go in, Jesse and Chad started stripping off layers and throwing them into the car.

“Is it warm in there?” I asked Matt, who was making no move to remove his grey, cotton hoodie.

“Yeah, it gets pretty hot when you’re in there,” he said, his words pouring out thick and slow with a southern twang, “but I don’t like to be cold. Even for a little bit.”

I nodded and decided to keep my sweater on this time around.

As our boots crunched their way into the mine, the blinding darkness of the night bled into an even blacker darkness of winding tunnels. The further we got from the entrance, the thinner the air felt as meters of mountain rock shielded us from the desert breeze outside.

Suddenly, Chad asked us to stop.

“Check this out,” he said, turning off his headlamp and motioning us to do the same. As the last of us flicked off our light, we were left in a darkness that words can’t describe.

I stood amazed, completely deprived of my sense of sight in a way I’d never experienced.

I listened to the sound of our breathing, felt the warm air of my lungs gather behind the bandana I’d tied over my mouth. Slowly the darkness filled me with a surreal sense of infinity — of being beyond what I could see.

When we flipped on our lights, I was almost surprised to be standing beneath a rock roof, next to a rusting, old mine cart.

The whole experience was so surreal. The darkness, the novelty, the movie-like setting gave the whole evening a dreamy quality that was hard to shake. Yet the feelings, the friendships that were already forming, the thrill of shimmying down mine-shafts and up rickety, wooden ladders, that all felt real. Refreshingly real.

The next morning I woke to the sun slicing through a crack in the curtains and bathing my face in its light. My muscles were throbbing and scattered across the floor were my clothes and boots, caked in a layer of mine-dust. The staff trailer was quiet except for the tumultuous snores emanating from Chad’s pretzel-like figure on the couch.

I crept past him to the door, eager to see the land I had met in the darkness of the night before. As my eyes adjusted to the light, my breath stopped short in my throat. All around me were graceful, bare-boned mountains made up of rocks of every color. They bled into one another like a geological rainbow and pointed up at the dark blue, cloudless sky above. The yellow ground framed their base and green shrubs spotted the entire way to the horizon. The silence I had embraced the night before was still there, wrapping me in its stillness.

“Magical, isn’t it?” Cynthia called out as she came out of her trailer to join me, a flock of dogs following at her heels.

I had met Cynthia – the namesake and owner of these desert lodgings – only briefly the night before and had already decided that she was an impressive anomaly of a woman. She was small and sturdy-looking, with a toughness of body and spirit; but there was a gentleness in the way she spoke that drew you in like sorcery. Living in the desert means braving some of the harshest conditions out there, but Cynthia bore them all in style. I never saw her without her hair perfectly arranged in a well-groomed twist and an outfit that could stand in the pages of Vogue.

As she walked toward me now, she was wearing a checkered suit with pointed shoulders and a flashy silver necklace that made the world around us feel very expensive.

“Have you gotten all settled in?” Cynthia asked.

I nodded, “Feels like home already.”

The desert is the perfect place to start from scratch.

“Everyone seems freer here,” I mentioned to Cynthia one day, my second week there.

We were winding along a desert road, her jeep rocking us dramatically in our seats at the whim of the rocks under its wheels.

“What do you mean?” she asked.

“No one seems to put up a front.” I said, struggling to express the phenomenon I was witnessing, even in myself, “We’re all wild and weird and unpolished.”

“Oh, that,” she nodded, understanding what I was getting at.

She waved a hand at the bare, dusty wilderness around us, “Look around. There’s nowhere to hide here. You have no choice but to be yourself.”

I wondered if a landscape could really have such a poignant effect on a community. Are our personalities really so reactive? If a barren land made a person more open, would a forest community — by default — be shrouded in secrecy? I thought through all of the places I’ve lived and decided the rule didn’t necessarily translate. Still, there was something about this land.

It was the way Chad yelled out at the mountains just to hear his echo. It was the way Matt never spoke unless he wanted to. It was the way Cynthia shared her fears and frustrations without hesitation. No one ever seemed to make small talk in the desert. You said what you wanted to say and that was that.

By the time I’d made it out of the mines that first night, I could already tell my filter was beginning to fade. I was saying things without thinking; musing about whether aliens were real and singing at the top of my lungs. The facade I’d spent years making for myself was fading away, leaving the weird, jumbled soul that lives underneath completely exposed. Which, in some ways, was exactly what I’d been searching for.

A few months before I came to Cynthia’s, I was living in Austin, Texas, working two part-time jobs and feeling generally numb to the excitement of life. I’d always had big dreams and creative aspirations, and suddenly I was drifting through life on a river of uninspired monotony. I knew I needed a change, a fresh start, something big. So I cut ties. I packed everything I needed into the trunk of my sedan and hit the road.

“Where are you going?” people would ask.

“West,” I’d say.

They’d laugh for a moment, waiting for me to continue, but in truth, that was all I knew.

I always loved watching old westerns with my grandparents. Sure, they often made me cringe with their outdated notions of race and gender, but they were also chalk-full of characters whose identities were tested in the face of grand adventures. The lawlessness of the wild west forced people to find their own morality, the isolation pushed people to unprecedented resourcefulness, and the wideness of the land gave them boundless freedom.

Living in the desert gave me a taste of what I’d thought was a purely fictional world.

My first night in the mines, we didn’t manage to find the second entrance. It took many more nights of wandering miles of round, rock-walled tunnels, slithering up dirt-covered inclines and balancing on mine tracks that stretched across the open air before we found the right path. Many nights we’d feel the soft breath of a chilly breeze and think that we must be close only to reach a dead end. We hit our helmets on rocks and scraped our knees and cursed at the obstacles in our path and still pressed on — loving every second of it.

Even when we finally found the ladder that would lead us out the back side of the mine, we had one last test of courage to face. Halfway up the thirty-foot climb, we were joined by some very large and very curious rats. They scampered across the wooden rungs and sniffed our fingers. The walls of the tunnel hugged the ladder closely, leaving just enough room for rats to brush against our backs as we climbed.

As I emerged from the tunnel onto the side of the mountain, I shook off the jitters with a Chad-like howl to the sky. It was dark and moonless, just like the night I’d first arrived. But I knew the lands around me now, and I was beginning to know myself.

Leave a comment